In April 2015 I went on a road trip to Donegal to try and get into all seven of Liam McCormick's churches, with sunny weather on my side, in two days. I failed my mission entering six of them. At least it gives me an excuse to go back to Donegal.

McCormick designed more than thirty churches including three in England.with his first Church design dating from 1947 (Church of the Lady & St Michael’s Ennistymon Co.Clare) to 1988 St Joseph’s Surrey, UK. Huge liturgical shift occurring around the Second Vatican Council 1962-65 (Ellen Rowley ‘Admitting the Light’ The Furrow, Vol. 60 No.9 (2009), pp.502-506).

The life of Liam McCormick crosses geographical and religious borders and although a good friend of John Humes he consciously kept his political opinions private. Born in Derry, he grew up as part of a small middle-class Catholic community in the fishing village of Greencastle, Co. Donegal and where he lived for the large part of his life with his office in Derry city. Like his grandfather, McCormick was elected Lord High Sheriff for Derry city in 1970-71. He was a boarder at St Columb’s College in Derry from the age of ten. It was at St Columb's that McCormick met many of the clergy who were responsible for his later church commissions. After completing second level he graduated with a Diploma in Architecture from Liverpool in 1943 and worked for two years in the City Surveyor’s office in Derry designing air-raid shelters and housing projects and then spent a year as an architect to Ballymena Council (Simon Walker ‘Historic Ulster Churches’ QUB, Belfast, 2000, p.185).

Another St Columb's boy Frank Corr, also studied architecture in Liverpool and after graduation the two of them established Corr & McCormick. While in Liverpool his year went on many trips including the World Fair in Paris in 1937, being exposed to modern style pavilions by the likes of Le Corbusier.

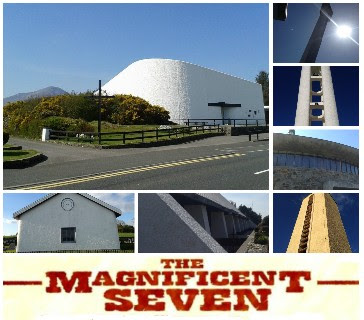

Seven of these churches are in his home county of Donegal, built in the landscape he knew best. A landscape which at the time had little or no concept of Modernism. Taking his influences from multiple sources it was his straightforward approach of simplicity and honesty of materials which made him stand out.

St Peter's Church, Milford (1955-61)

St Patrick's Church, Murlog, on the outskirts of Lifford (1960 - 64)

External mosaics by Oisín Kelly

Our Lady Star of the Sea, Desertegney, near Linsfort (1963-64)

This is my favourite of the Donegal churches. It was difficult for us to find as nobody we stopped to ask for directions had heard of it until we struck gold with a French woman who worked at a petrol station deli. After architecture sailing was McCormick's big passion. This church was one of his favourites as he could sail past it in his boat Diane. It's curved walls and roof form gives it the appearance of an upturned boat.

Church of St Aengus, Burt (1964-67)

The best known of McCormick's buildings and voted Building of the Century by a national poll. Burt won the RIAI Triennial Gold Medal in 1970.

Nearby Grianán was the inspiration behind the circular form of the church.

St Michael's Church, Creeslough (1967-71)

St Conal's Church, Glenties (1970-74)

Donoughmore Presbyterian, Liscooley (1975-77)

In an interview with Maev Kennedy of The Irish Times in July 1978 McCormick acknowledges that where modern architecture has failed is in its over-dependence on utility and function. He said that modern architects have learnt a lesson from earlier failures: 'We no longer believe in the omnipotence and validity of functionalism as such, but seek in our work the synthesis of a rational approach and artistry.'

As far as McCormick was concerned: 'Churches are important buildings, and not just religiously. Often a church is the only real architecture people will experience. It is important that they be right and correct.'

I can't recommend enough getting your hands on this compendium of eight books by Carole Pollard on the career of one of Ireland's greatest.