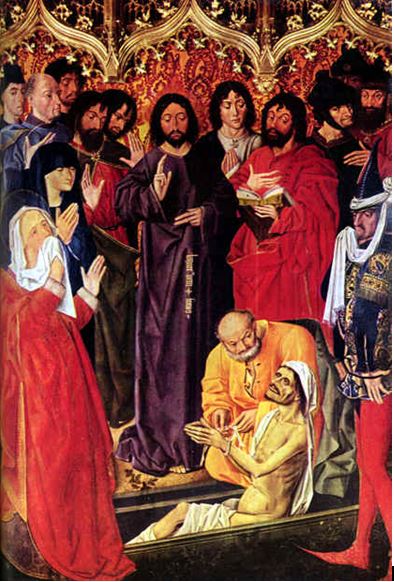

Taking a little detour from buildings I am looking at an object held within one of Limerick city's landmark's the Hunt Museum, formerly the Custom House on Rutland Street. My childhood has forever embedded thoughts my mind at this time of year around God, his mortal son and the Holy Ghost. Furthermore with his red robes this God the Father bares a likeness to what our modern society has replaced all that with- Mr Santa Claus.

The Late Gothic/ Early Renaissance

panel painting God the Father (h50 x W42 cm)[1]

attributed to Nicolas Froment is housed in the Treasury in the Hunt Museum, Limerick France which adds to the mystery of

this fragment of the altarpiece.

Nicolas Froment, French painter and

draughtsman, was born in Uzés (Languedoc ),

Picardy, twenty-five miles west of Avignon

most likely in the year 1435.[5]According

to Uzétian local legend, Froment’s father was the

barber and ‘homme de confiance’ of a bishop of Uzés[6]

which would explain how this young man with no connections and no family

precedent of an artistic career could have received papal commissions. It is

difficult to estimate his date of birth as well as the particulars of his early

life due to the lack of information available on Froment prior to the 24 June

1465 when he is recorded as being an inhabitant of the Languedocan village of Uzés

near Avignon .[7] By

1468 he was a permanent resident of Avignon

as he was recorded as paying rent on a house owned by a local barber.[8] It

was in Avignon

that he would live and work for the rest of his days up until his death in

either 1483 or 1484.[9]

His active life is recorded as starting in 1450[10]

with his first signed and dated work the Resurrection

of Lazurus (1461)[11] (175 x 200cm; Uffizi, Florence) as the 18 May 1461[12]

which is the date inscribed on the triptych’s exterior wing frames.[13]

Froment was probably a master at the time as apprentices were generally

forbidden by guild rule to sign works on their own.[14]

However Froment’s name has not been found in Netherlandish guild lists of the

period. Nevertheless he could have worked without guild affiliation as a court

painter. The altarpiece was commissioned by Francesco Coppini, Bishop of Terni

and Pal Legate[15] who is

depicted on the exterior wings praying to the Virgin. He brought back the piece

to Italy

in early 1462[16] where

he gave it as a political gift to Cosimo de’ Medici[17]

who donated it to the Franciscan convent of Bosco ai Frati in Mugello just

before his death in 1464, when it remained until the late eighteenth century.

During this time in the Netherlands Froment has also been ascribed, in

collaboration with Jacques Daret of Tournai, cartoons for tapestries produced

in 1460 for Guillaume de Hellande, Bishop of Beauvais[18]

(Beauvais Cathedral; Boston ,

Mus.). Also attributed to Froment and in a related style are a Mourning Virgin, a fragment on oak of a

larger panel and a drawing with the upper part of a ‘Transformation.’ In 1470[19]

he was commissioned by Catherine Spifami, widow of Langier Guiran, to paint an

altarpiece of the Death of the Virgin

with SS Mary Magdalene and Catherine with donors on the wings, for a chapel

appended to Notre-Dame-de-Consolation in Aix-en-Provence .

He is also supposed to have painted the Martyrdom

of St. Mitre (Aix-en-Provence ,

St.Sauveur), a commission for Mitre de la Roque, a merchant, for his funery

chapel. In 1471-2, on commission of the spice merchant Pierre Marin, Froment

produced a window of the Annuciation for the choir of St.

Pierre at Avignon .

In 1473 he designed the embroideries for the uniforms of Avignon’s couriers and

props for ‘tableaux,’ including the ‘Temple of Jerusalem’ erected for the entry

of the papal governor Charles II of Bourbon.

In

1476 Froment painted 204 shields that included the arms of the Papal Legate

Giuliano della Rovere. The following year the city ordered from the artist

fourteen ‘écheafauds’ for the feast of Corpus Christi, including scenes of the

‘Temptation of Christ’, the ‘Annunciation’ and the ‘Story of Gideon’ Froment’s

work for the Town Council attracted the attention of René I, Duke of Anjou in

1475 who would remain his primary patron until his death in 1480.[20]

It is during these years that Froment produced his major work, the triptych of

the Burning Bush (410 x 305cm; Aix-en-Provence ; Cathedral

of St. Sauveur). In this piece Froment illustrated his application

of the Flemish style to the landscape of Provence

which explains why at one time the triptych was wrongly attributed to Jan van

Eyck and to Jan van der Meire in the nineteenth century. If wealth is a measure

of an artist’s success than Froment was successful enough to purchase three

adjacent houses on the corner of place Piuts-des-Boeufs near the Papal Palace Avignon around 1450. They formed the core of

the realists of the school of primitive artists of Provence and are credited with introducing

Flemish naturalism into French art.

This

painting in the Hunt museum is most likely a small section of a much larger

wooden altarpiece with its dedication being to the Trinity.[22] It

could have been the central panel of a triptych commissioned by René I for his

private chapel at his residence in Aix-en-Provence ,

as a visual compliment to the altar.[23]

It is ambiguous why this part would be removed and of the whereabouts of the

remainder of the altarpiece. It is not an uncommon occurrence and it could be

due to the tightened restrictions placed upon church adornments during the

Catholic Reformation. This movable, functional piece would have been placed

either in front or hanging above the altar playing a vital visual role during

the moment the priest holds up the Eucharist during the act of

transubstantiation as a focus for worship. The Trinity would have been

particularly effective in this respect as the image of Christ would remind the laity

of his sacrifice and of the promise of salvation.[24]

The altarpiece’s other general purpose would have been to teach the illiterate

churchgoers the concept of a three-personed God. Historically Froment would

have been painting this altarpiece only a century after ‘The Great Schism’ of

the church when the Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox branches split even

to this day over differing doctrinal interpretations of the bible with one of

the main arguments being the Trinity. The word ‘trinity’ itself is not stated

in the New Testament but the concept of it is mentioned in Matthew 28:19.[25]

This was defined at the Council of Nicaea in 1439 so it was a fairly topical

subject for Froment to depict. A commission for an altarpiece was quite a

common phenomenon in the fifteenth century largely due to the result of the

growing initiative of non-ecclesiastical and non-aristocratic patrons. It is

possible that, like the Burning Bush,

René’s image could have adorned the side panels alongside his chosen patron

saints. René, like all patrons, would have had his favourite saints and in

return for the special devotion paid to them. The saints were expected to plead

the cause of their devotees in the court of heaven, reducing the individual’s

allotted period of suffering in purgatory.[26]

The Catholic Reformation the following century put strict restrictions on such

practices.

Analysis

of the design itself reveals that it is Netherlandish in its realism and

attention to small details such as the effect of light falling on individual

hairs on his long white beard. This work is figurative and vertical in

orientation. God is depicted bare-headed which is quite uncommon but a good way

to portray old age. However the provincial origin of Froment emerges in the

harsh rendering and the stiffly-posed figure and angular folds on his robes.

The human portrayal of God is out of proportion as his head is clearly too

small for his body. It is an old man floating in a two-dimensional space

against a plain gold background which is reminiscent of Robert Campin’s Seilern Entombment. Volume is not

suggested through shadow or shading but instead through colour. God is wearing

a rich red robe, the colour of royalty indicative of a god sitting on his

heavenly throne, beneath a blue mantle[27]. The

attribution to Froment would be based on the occurrence of this red colour in

another of Froment’s documented paintings. Other characteristics that indicate

that this is a Froment painting or a follower of his are God’s sunken cheeks

which can be seen in the various figures in The

Resurrection of Lazurus, and his grimacing, down-turned corners of his

mouth. This style of facial expression is considered to have been influenced by

styles which do not survive. [28]

Of course this was painted in an age of a judgemental god demanding our awe and

reverence. His facial expression fits within the theory that this is the upper

part of a Trinity similar to Masaccio’s (1401-1428) The Holy Trinity, the Virgin, St. John

and donors (Santa Maria Novella, Florence, 1427). God is showing the viewer

his only son, possibly on a crucifix or else as a lamb, suffering for all our

sins. The dove representing the Holy Ghost would be between Father and Son with

its wings spread as if about to take flight. It was only towards the latter part

of the fourteenth century[29]

that God and Christ began to be differentiated from each other pictorially.[30]

Before this Father and Son were seated beside each other with identical costume

and features[31] and

even portrayed in some cases as the same age. Once separated Christ was bear

torsoed and given the marks of his suffering with the crown of thorns and the

cut on his side. This began the

tradition of the bearded old man in plain robes to reinforce the idea of all

people, rich or poor, being the children of one universal father. God too began

to assume a larger body in relation to Christ. Perhaps denoting importance as

the creator of all life. The difficulties of representing the three entities of

God had been largely resolved by the fifteenth century although the church was

still uneasy about how the theological complexities were rendered visible by

artists.

Iconographically

the Holy Trinity is probably the most well known art motif and also the most

complicated. The difficulties of representing three persons in one god had been

resolved by the time Froment was painting this trinity.[32]

However the Catholic Church was still uneasy about images such as these

bordering on idolatry.[33]

The use of images was another issue that split the Eastern and Western Churches

As for its place within the western canon of art Froment’s painting is

in the group of works after Masaccio’s famous fresco The Holy Trinity (667 x 317cm). This painting was to have a huge

affect on artists that came to Florence

for the next two hundred years. More than likely Froment was aware of this

painting and, as already stated, his Trinity is thought to be in the style

similar to Masaccio’s with the composition symmetrically centred on the body of

Christ. The next major work of this kind would have been Fra Angelico’s Virgin and Child Enthroned with SS John the

Evangelist, John the Baptist, Mark and Peter (1433-6; Florence, Mus. S.

Marco). Examples of Froment’s contemporaries depicting the Trinity are

Enguerrand Quarton in France

with his Coronation of the Virgin and

in Germany the Polish artist

Jan Polack (1435-1519) with Gottes Not

(200 x 155cm; Munich ,

Bayer. Nmus.). Later generations within this same genre would be Albrecht

Dürer’s(1471-1528) Adoration of the Most Holy Trinity by the Communion of Saints( 135

x 123cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Mus.) in

1511 and the Spanish artist José de Ribera’s (1591-1652) Holy Trinity in 1635(226 x 181cm; Osuna, Mus.A Sacro). This last

example follows the same order of God the Father bearing the weight of Christ

but this Christ is of the Caravaggio tradition of the weighty figure drenched

in light and wearing his blood-soaked loin cloth. These works show the natural

progression of increasing realism and pathos.

Although never large in terms of population, Uzés was a town of

historical significance and contemporary importance in the fifteenth century,

when Froment would have been growing up there. Originally a primitive campsite

and then a Celtic settlement,[41]

its location on a limestone plateau above the Alzon Valley Church of Languedoc

Froment in all probability had launched his

artistic career in Avignon

by 1465[43]

then a bustling, affluent cosmopolitan area of around 100,000 inhabitants.

Conditions there could not have been better for a talented young artist with

good credentials, as painting in particular thrived.[44]

The departure of the popes from Avignon

was in no way detrimental to the activity of the important community of the

artists that had developed in the city during the reign of the papacy there

from 1309-1377.[45] Over

the next century or so, churches continued to be built and embellished, private

residences of aristocrats, wealthy merchants and religious continued to need

renovation and decoration, and the Palais des Papes itself continued to be

renovated and expanded, first by the antipopes (1378-1419)[46]

and then by the papal legates and governors appointed by Rome to rule Avignon

as an Apostolic Seat. Froment’s Avignon contemporaries would have included such

artists as Enguerrand Quarton from Laon, Pierre Villate from Limoges, Thomas

Grabuset from Besançon, Armand Tavernier from Lyon, Martin Pacaud from Bourges

and Jacques Paperoche from Picardy.[47]

In spite of their diverse origins, they collaborated on commissions from the

city fathers and from private patrons, and they received individual commissions

from the same patrons such as René of Anjou. Thus stylistic influences and

resemblances among the works of these Avignon-based artists must have been

sufficient to define a “school” for that particular point in time, even though

its exact nature is unknown.

New

Netherlandish influences enriched the earlier Italian trends to produce this

school of painting that was at once dramatic and richly detailed.[48]

Comparatively few Provencal works from the fifteenth century are still extant

and an even smaller number are connected with known artists or are precisely

dated. This lack of knowledge about the specific artistic atmosphere

encountered by Nicolas Froment in Avignon in the mid 1460s contributes to the

difficult problem of identifying sources of influence that might have caused

Froment to put so much stylistic distance between his ‘Lazurus’ done in the Netherlands in 1460-1, and his Burning Bush done in Avignon or Aix

around 1475-6.[49] What is

known about the period immediately following his return to the south of France

is that Froment’s reputation as an artist grew and spread rapidly.

To

put this work into context, patronage was vital to artists back then but as a

result of the outbreak of the Hundred Years War (1337-1453) political

instability among the Valois princes led to a

decrease in Royal commissions for artwork.[50]

However the Court of René I, (1409-1480) (4th of Duke of Anjou (Duke

of Lorraine; Titular King of Naples and Sicily , Hungary

and Jerusalem )[51]

to give his full title, became an important artistic centre in mid fifteenth

century France .

René I held his residence in the city of Avignon

and was Nicolas Froment’s principle patron from 1475 to 1480. His family

connections were impressive as he was the brother-in-law to Charles II, King of

France and the father-in-law of Henry VI King of England .[52]

The variety of his domains from western and eastern France

to southern Italy

influenced the art he commissioned. His enforced stay as a prisoner of Philip

the Good, Duke of Burgundy during the struggles for Bar and Lorraine (1431-2, 1435-7) most likely

brought him into contact with Netherlandish painters. The earliest record of

the artist-patron relationship between Nicolas Froment and René is an entry in

the accounts kept by René’s treasurer, Jean de Vaux, for the year 1476.[53]

His first commission was the iconographically complex Mary in the Burning Bush in 1475[54]

which now hangs in the south wall of the nave of the Cathedral of St. Sauveur

in Aix-en-Provence .[55]

This triptych depicts René of Anjou and his second Jeanne of Laval[56]

with several saints and was originally made for the Church of the Grands-

Carmes in Aix,[57] where

it hung until the French Revolution. This altarpiece also depicts God as a half

figure, in a carved panel above the central scene.[58]

On the exterior wings of the altarpiece, the archangel and the Virgin stand in

niches of a masonry wall.[59]

Several entries appear in René’s accounts of 1477 for payments made to “maistre

Nicolas peintre”[60] but it

is not until 14 November 1477 that an entry occurs with the full identification

of this artists as “Nycolas Froment, paintre du Roy de Sicille.”[61]

The Hunt Museum

The

time and place of their first meeting is unknown or how Froment was brought to

René’s attention. Nevertheless it has been speculated that René was a painter

himself and that the young Froment was his protégé therefore developing his

Netherlandish style to please the taste of his master but there is no evidence

to back this claim. It is known however that René was in Provence

from December 1437 to April 1435, October 1442 to February 1443,[63] in 1453-4 and again from May 1457 until

January 1462 and that he made visits to Avignon

during these periods. René could have possibly encountered Froment’s many

artistic works for the Town Council and it is also believed that Froment might

have worked on the house and chapel of the Bishop of Uzés, Jean de Mareuil in

1465 bringing him to the attention of local officials.[64]

If Froment was not brought to René’s attention in the 1460s he would certainly

have moved into René’s social sphere when he was called from Avignon to Aix in early 1470 to work for

Catherine Spiefami Guiran, widow of Lanugier Guiran[65]

to paint an altarpiece. Froment must have flourished under the direct exposure

of René who was a serious literary scholar, linguist, writer, poet and painter.[66]

It is René’s writings on a variety of subjects such as religious morals (Mortifiement de Vauvie Plaisance[67])

that distinguishes him from most contemporary patrons. From 1477 onwards[68]

Froment was working exclusively as René’s ‘peintre du roy’[69] a

position once held by Barthélemy d’Eyck.[70]

Aside from the general decoration of the Avignon

premises of the duke, Froment continued to produce individual paintings for his

patron. He was paid by René for ‘certain paintings which the said lord has

devised’[71] which

could indeed include God the Father.

Unfortunately,

apart from the Burning Bush, the Naval Combat of Turks and Christians is

the only painting produced for René by Froment which is identified by subject

matter in the accounts of payment.[72] A

portrait diptych of René and his wife known as the Matheron Diptych (1476) [Appendix C]preserved in the Louvre since

1891, is widely accepted as a work of Froment or his studio.[73]

Nicolas Froment’s last known task for the duke was the repainting of his horse

armour in November 1479.[74]

The death of the duke on 10 July 1480 undoubtedly had serious consequences

throughout the Provencal artistic community. In hindsight this event can be

seen as a catastrophe for Froment who devoted five years of his life to satisfy

René’s artistic needs. Froment, who had maintained his residence and workshop

in Avignon

during the René years, reverted back to his status as an independent artist.

Only two commissions are recorded as being completed by Froment after his court

career with both of them being from the city of Avignon . Therefore Froment’s attempt to

regain his former level of professional activity was probably not successful.

The

materials of this piece are typical of the age. It is executed on an oak panel[75]

which would have been the most suitable wood for a triptych for its stability

and durability. The type of wood employed can be used in determining its

origins.[76]Oak was

used almost exclusively in the North for panel painting in the fifteenth

century onwards as opposed to other softer woods more frequently used in the

south of France and in Italy such as walnut, poplar, pine, spruce, cherry, etc.[77]

Although the use of oak is not positive evidence in itself of the Northern

origin of a panel painting but oak panels have been called “l’essence- type des

écoles de Nord.”[78] On a

summation graph for panel painting in various European countries in the

fifteenth century Jacqueline Marette lists Italy ’s over-all usage of oak at

just 1.5%.[79] Poplar

was employed in Froment’s only other documented work Burning Bush (1475) and the Matheron

Diptych. Before the actually painting could begin the panel had to be first

coated with a white plaster providing the artist with a highly polished surface

on which to paint.[80] God the Father was done probably in a

mixture of egg and oil tempera to bind the pigments hence the fine network of

cracks that can be seen on the painting’s surface especially on the gold

background. The use of gold was to denote the patron’s wealth as it was in

short supply in Europe by this century. It was

in the middle of this century that novel oil painting methods were being

introduced from Northern Europe . In these

transitional years the egg medium was often used in combination with separate

layers of oil-based paints, either for lighter coloured areas or more

particularly as a quick-drying under-paint for subsequent oil-based glazes. Depending

on the number of layers a panel painting with take several months[81]

to complete when the drying-period is taken into consideration. The painting is

in overall good condition and small cosmetic defects such as varnish been too

glossy or relative humidity damage (RH) are stated in the collection survey

form.[82]

This

work is displayed on the ground floor in the room known as the Treasury and, as

with the rest of the Hunt Museum, it groups its objects by genre. Along with

Froment’s God the Father this room

includes other religiously themed works of special interest such as The Galway Chalice, The St. Patrick Reliquary Bust and The Bernardo Daddi Crucifixion Scene. This panel painting is hung

behind glass in an alcove in the shape of a Gothic arch. Within this individual

display is The Arthur Chalice which

is housed on behalf of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Limerick. The Treasury is

a great example of how some museums try to place an object within its original

intended cultural setting. This is important as it cannot be forgotten that

this work is a functional piece and was never intended to be looked at for its

aesthetic value but to draw awe from its viewer. Its bright rich colours and

gold background were meant to jump out from its dark, solemn surroundings in a

Gothic church which would have had little natural light, recreated here by the

museum. There is clever use of light with just the one, almost celestial light

source coming from above the painting. The impact of this painting would have

been lost if it was placed on a white wall along with its artistic and

religious heritage. The painting itself is framed within what looks like a

temporary hard wood frame that has been amateurishly aged with dabs of yellow

paint when viewed up close. The frame’s inappropriateness was noted in the

collection survey form[83].

Promotion of this painting is

important as it can facilitate the viewer’s understanding of fifteenth century

Western culture. Museums of all kinds play vital roles in the characterization

and evaluation of cultures[84]

and it is their duty to communicate this information to the public as the

museum needs the public just as much as the public need the museum. The

Treasury is a fascinating collection of religious relics, paintings and

especially altarpieces. Even in our modern world where religion does not play

as large a role in our lives as it once did, it is still beneficial to see how

the lives and sacrifices of various saints, the sacraments of mass and the

afterlife weighed heavily on their minds. It moulded their lives and their

interactions with each other; it was part of their weekly ritual as well as

providing a gathering place for the community. This work should be promoted as

a glimpse into a culture that was dictated by the Church which has resonance

with our own country as the same could be said of Ireland up until at least the

1960s. One does not have to be particularly religious or spiritual to

appreciate the craftsmanship that went into assembling this altarpiece.

The

people of Limerick are very fortunate to have such an historic artefact on

their doorstep by an artist who has work exhibited in galleries in France , Italy

and the United States .

As with most things public taste in art goes round in cycles as Froment and

other Gothic ‘primitive’ artists gained popularity in the Victorian era as with

all things Gothic and again in the 1930s when John and Gertrude Hunt began

collecting around Europe. Limerick is

concentrating its efforts more and more to promoting its medieval heritage so

hopefully it will start to showcase Nicolas Froment’s God the Father and similar works.

[1] Art Treasures in Thomond held

at Limerick Art Gallery, (Limerick, Limerick Leader, 1952), p.3.

[2] According to John M. O’Connor, Solicitor to Trudy Hunt [interviewed

21 May 2007] http://www.ria.ie/pdfs/huntreport.pdf

[3] Helen Armitage, The Hunt Museum ;

Essential Guide, (London

[4] Patrick F. Doran, 50

Treasures of the Hunt Collection, (Limerick, The Hunt Museum Executive,

1993).

[5] This is based on the

assumption that Froment had completed his apprenticeship and was of legal age,

i.e. twenty-five years or over, by the time he received his commission to paint

the Resurrection of Lazarus in 1460.

[Marion Lou Grayson, The Northern Origin

of Nicolas Froment’s ‘Resurrection of Lazurus’ Altarpiece in the Uffizi Gallery,

(PhD. diss., Columbia Uni., 1979), p.6.

[6] Baronne de Charnisay ‘Les chiffres de M.

l’Abbayé Rouquet: Étude sur les fugitifs du

Languedoc [Uzés]’, Bulletin de la Société

de l’Histoire de Protestantisme Français, lxv, 1916, p.138.

[7] Marion Spears Grayson

‘The Northern Origin of Nicolas Froment’s Resurrection of Lazarus Altarpiece in

the Uffizi Gallery, The Art Bulletin, Vol.

58, No.3, (Sept.,1976),p. 350.

[9] The last record of the

living artist is a distribution of grain made to him on 21 March 1483 by Paulet

Heydine, treasurer of grain in Avignon .

He was definitely deceased by 23 Dec 1484 when his property was sold. [Ibid.].

[14] Charles Sterling. ‘Tableaux Français

inédits: Provence’, L’Oeil, 425,

(Dec., 1990), pp.46-53.

[17] Groveart.

[18] F. Joubert, Jacques Daret et Nicolas Froment: Cartonniers de tapisseries, Rev.

A, 88, (Paris, 1990), pp.39-47.

[19] Britannica Encyclopaedia

Online 2007. [12 Nov. 2007].

http://www.britannica.com/ed/article9035490/Nicolas-Froment

[20] Patrick M. de Winter.

Grove Art Online. Oxford

University

[24] Marilyn Smith,

‘Altarpiece.’ Grove Art Online. Oxford

University

Baptizing them in the name of the Father

and of the Son,

And of the Holy Ghost.’

[26] Alexander Nagel

‘Altarpiece,’ Grove Art Online. Oxford

University

[34] Ursula Rowlett,

‘Popular Representations of the Trinity in England , 990-1300,’ Folklore, Vol. 112, No.2, (Oct., 2001),

p.207.

Suddenly the heavens were opened to him

and he saw

The Spirit of God descending like a dove

and alighting on him.’ [Tim Dowley (ed.), A

Lion Handbook; the History of Christianity, (Edinburgh, 1996), p.334.

[40] Don Denny, ‘The

Trinity in Enguerrand Quarton’s Coronation of the Virgin,’ The Art Bulletin, Vol. 45, No.1, (Mar., 1963), p.49.

[44] Paula Hutton, ‘Art Life and Organisation.’ Grove Art Online. Oxford University

[45] H. Chobaut, Avignon et le Comtat Venaisin, (Paris, 1950), pp.51-3.

[50] A. Demarquay Rook,

‘René I, 4th Duke of Anjou ,’

Grove Art Online. Oxford

University

[55] Britannica

Encyclopaedia Online 2007. Assessed 8 Nov. 2007.

http://ww.britannica.com/ed/article-9035490/Nicolas-Froment

[58] Emily Harris, ‘Mary in

the Burning Bush; Nicolas Froment’s Triptych at Aix-en-Provence ,’ Journal of the Warburg Institute, Vol. 1, No. 4, (Apr., 1938),

pp.281-86.

[59] Charles I. Minott, ‘A

note on Nicolas Froment’s “Burning Bush” Triptych,’ Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institute, Vol.25, No.3 / 4,

(Jun.-Dec., 1962), pp. 323-325.

[62] Armitage, Hunt Museum, p.29.

[63] Yoshiaki Nishino, ‘Le Triptych de

l’Annonciation d’Aix et son Programme iconography,’ Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 20, No.39, (1999), pp.55-74.

[64] L.H. Labande ‘Notes sur quelques

Primitifs de Provence Part II: Nicolas Froment,’ Gazette des Beaux –Arts, IX, 1933, p.86, n.1.

[68] Charles Sterling, ‘Nicolas Froment,

peintre du nord de la France’ Études

d’art medieval offertes á Louis Grodecki, (Paris, 1981), pp.325-36.

[69] Grayson, p.62.

[70] M. Laclotte and D. Thiébaut, ‘L’Ecole

d’Avignon,’ (Paris, 1983), pp.219-20.

[71] Grove Art

[72] F. Perrot, J.L.Taupin and F. Enaud ‘Le

Roi René Avignon’, Archéologie,

No.73, (August, 1974), pp.21-38.

[75] Patrick M.de Winter,

‘Nicolas Froment’ Grove Art Online. Oxford University

Press.[7 Nov.2007], http://www.groveart.com

[77] Jill Dunkerton, ‘Panel

Painting,’ Grove Art Online. Oxford

University

[78] Jacqueline Marette La Connaissance des primitifs par l’etude du bois du xlle ai xvle

siècle, (Paris, 1961), p.74.

[82] Appendix A

[83] The Hunt Museum Collection survey form [4/12/96]. Museum Archives Ref

No: HM/ARCH/A1/01388(4).

[84] Peter Jones,’ Museums

and the Meanings of their Contents,’ New

Literary History, Vol. 23, No. 4, (Autumn, 1992), p.911.